What is in your genome?

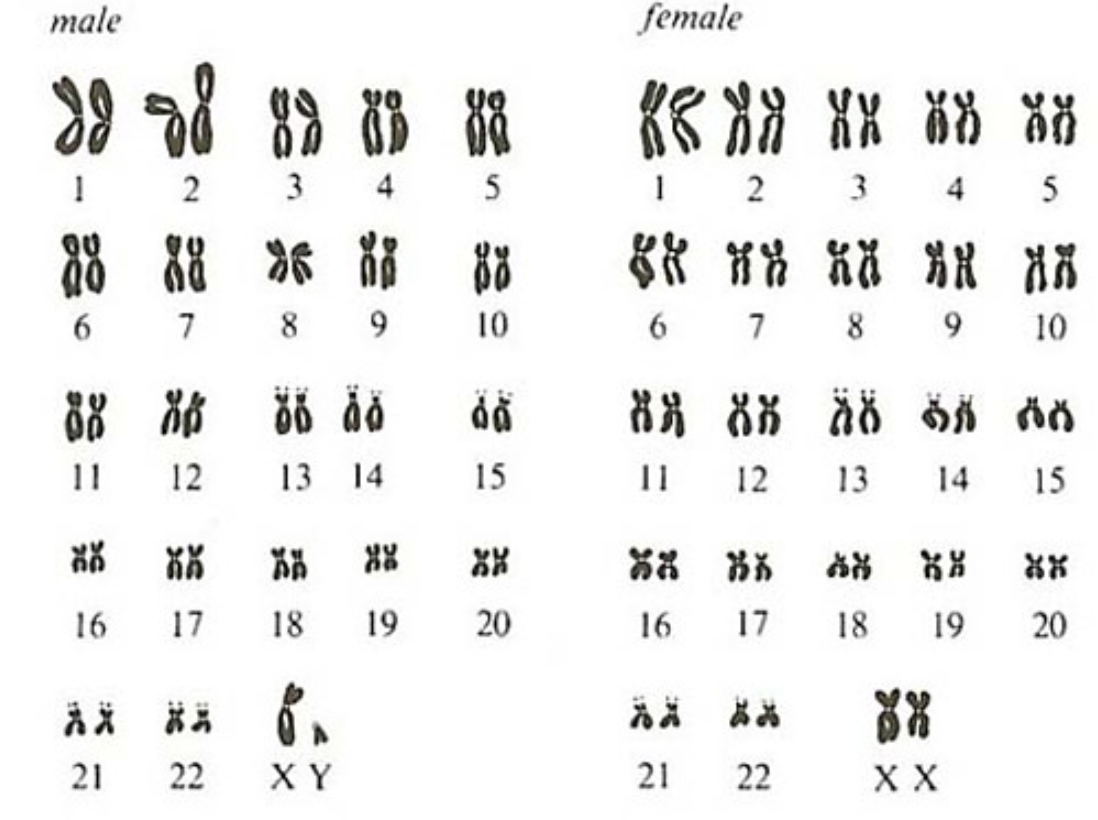

23 pairs of chromosomes

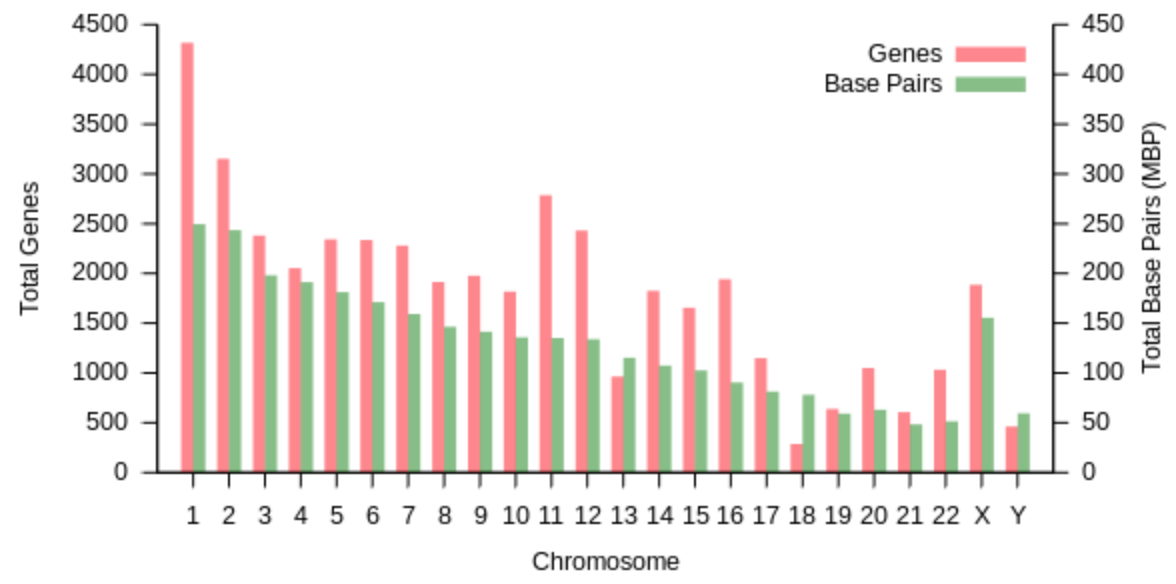

Each of us has 23 pairs of chromosomes. 22 are “autosomes” (non-sex chromosomes) and 1 is an “allosome” (sex-chromosome). Females are “XX”, and males are “XY”. The X chromosome has ~800 genes and just shy of 154 million bases, and the Y chromosome is significantly smaller, containing only ~50 genes and ~57 million bases.

In females, one X chromosome is “silenced” (turned off) through a process called x-inactivation, so that they do not produce twice as many gene products (males only have one X chromosome).

The 1st chromosome is the largest, with over 247 million base pairs and ~2000 genes. They are generally organized from largest to smallest. The smallest chromosome is 21, with ~47 million bases and ~200 genes.

~20,000 genes

The human genome contains about 20,000 genes. When the human genome was originally sequenced, there was thought to be many more genes, original estimates were upwards of 100,000 genes.

Genes are instructions for how to make proteins. Only 2% of the genome is “coding” meaning it produces a protein product via transcription and translation. The other 98% of the genome was thought to be “junk” but we’re just now discovering what the bulk of our DNA actually does. For instance, we now know a large portion of our DNA is “regulatory” DNA meaning the noncoding DNA “regulates” which genes should be turned on or off (expressed or not expressed) under certain conditions. For example, different genes are expressed (produced) during starvation to keep you alive, that would not have been turned on if conditions were different.

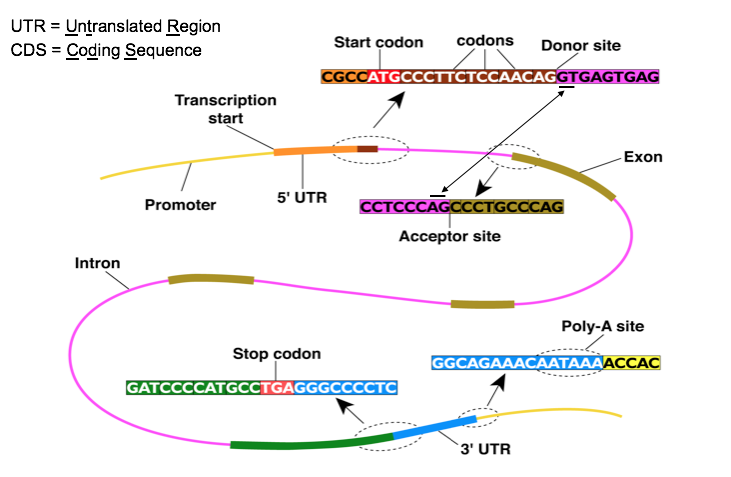

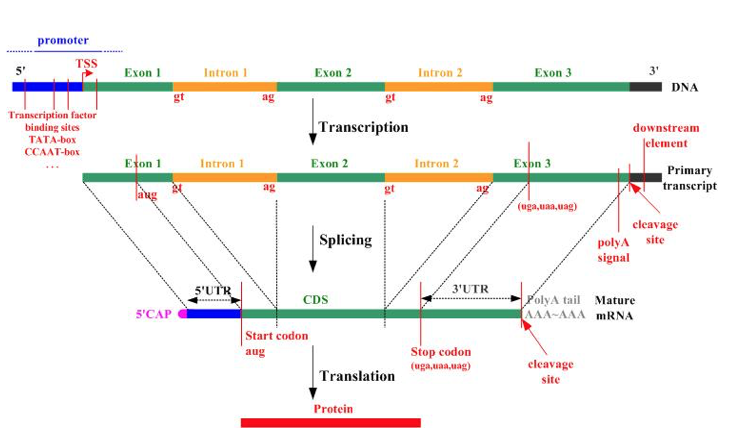

Anatomy of a gene

-

Introns - The pink parts of the gene, introns are NOT turned into a protein.

-

Exons - The ochre parts of the gene, exons are coding (turned into a protein).

-

The start and stop codons do what you would expect, they are signals to start and stop transcription.

-

The promoter regulates the level of transcription (how much of a protein is produced from a given gene). A promoter is a generally 100-1,000 base pairs long, and consists of a special sequences of DNA that transcription factors (proteins involved in starting transcription) bind to.

1 gene, many functions!

Part of the reason that the number of genes originally estimated was so far off, was because the idea of “alternative splicing” had not been discovered yet. One gene can turn into many proteins, by “splicing” or combining the introns and exons pictured below in different combinations.

The protein variants produced by alternative splicing end up having different functions because they end up having different “domains”. Protein domains are sequences that fold independently of the rest of the sequence.

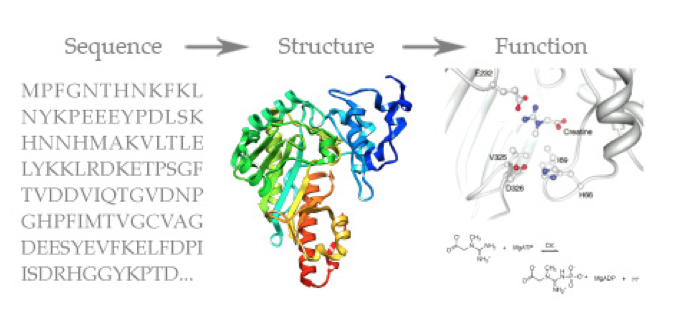

The DNA sequence gets parsed into an amino acid sequence, and the sequence of amino acids together form a chain (called a polypeptide or protein), and this protein’s shape (structure) is determined by it’s sequence. The structure of the protein then determines the function it will serve in the body (what other proteins will be able to fit/bind with it, etc).

Interesting computational puzzles

- How do you predict where the boundaries of genes lie?

- Rule based programs exist (GeneFinder), neural network based programs (GrailEXP), and hidden markov model based programs (Genscan) exist today.

- How do you predict all splice variants given a gene?

- How do you predict protein structure, given an amino acid sequence?

- Many Nobel prizes have been awarded along these lines of inquiry!

3 billion base pairs

The human genome is 3 billion base pairs. Now that the human genome has been sequenced, the challenge that remains is interpretation. What do all these bases do? How do our genes confer health and disease?

Roughly we think the composition of the human genome is:

-

Genes 2%

-

Non-coding RNAs 2%

-

Regulatory DNA 10-15%

-

Repeats 40%

-

Other 40%

Before the next generation sequencing revolution, scientists thought the majority of human disease mutations would be in the coding regions. To their surprise, 80-90% of human disease GWAS associated SNPs are in fact non-coding. The majority of diseases are likely to involve issues in how genes are regulated.

“Genomics is as much a field of Computer Science, as it is a field of Biomedicine. There is the code, which is your genome, less than a gigabyte long. This piece of code “runs” every single cell in your body. And then there is you - the code’s output. A giant “cellular” automaton. Seen this way, the genome is the most fascinating distributed operating system on the planet. Human genomics is the study of how this operating system produces its output - you: Many human diseases are caused by “bugs” in this code. Humans differ in millions of places in their code. The bugs we want to flush out are often only a handful unfortunate differences. Technology is allowing us to see the genome in action, even intervene with it, rewrite sections at will. These are the first blossoms of a “genome IDE” (integrated development environment), that will change humanity forever. The genome also holds a fascinating record of how we became who we are today, at the code level. Of how other animals (successful source code forks) have become so different from us. And what code “modules” we may borrow from them to improve our own health. The knowledge of what “bugs” in our code will pain us the most, how best we may “patch” them (with drugs and procedures), how best to fix our bugs (genetic engineering) or “compile” only bug free versions (in-vitro fertilization). All of these will profoundly change humanity as we know it today. – Bejerano Lab

Thanks

Credit for the good stuff goes to Gill Bejerano – Associate Professor of Developmental Biology, Computer Science, Biomedical Data Science, and Genetics, mistakes are mine.