The Neuroscience of Free Will

This is a summary of the key results from five seminal papers on the neuroscience of free will, namely: Libet (1983), Fried (1991), Brass (2007), Lau (2007), Soon (2008).

Motivation

Society revolves around the belief in the presence of a conscious free will. It is at the heart of our conception of moral and legal responsibility. A central part of identity is the belief that we can “want” to do something, that we can have the intention to do something, and that our intentions then go on to drive our actions. Philosophers argue free will is the defining quality that differentiates us from other creatures - every animal gets hungry, but we (uniquely) can elect to restrain ourselves. The denial of free will denies one of the most basic aspects of human existence. Yet, many neuroscientists are convinced the topic is no longer open to intelligent debate: the data shows that free will does not exist. Neuroscientists believe that conscious experiences are consequences of brain activity, rather than causes (12). They argue our actions are initiated by unconscious mental processes long before we become aware of our intention to act (10,11,12).

Scientific inquiry has brought many unintuitive, startling, hard to stomach truths to light. The atomic theory challenges our sense of touch: objects feel solid, yet we know they are made up of mostly empty space. Kepler’s laws of planetary motion challenge our sense of balance and acceleration: we feel still, yet we know we are throttling through space at a thousand miles per hour. The big bang theory challenges our sense of credulity: we feel it is intuitively unfathomable for the entire universe to begin as a hyper condensed millimeter in space. Is it the case that we “feel” free will exists, yet it is another (illusory) trick of our senses? Have we been duped by our physiological faculties, our fallible human sensors, with distorted data that prevents us from seeing things as they really are?

In combating the question of free will, neuroscientists aim to characterize what goes on in the brain when we make a decision, to interrogate the sense or feeling of causing something, of being an active agent initiating as opposed to a passive subject responding. Social psychologists are concerned with what the effect a person’s belief (about free will) has on their behavior or willpower.

Defining “free will”

Free will is a difficult concept to define. We can start to define free will by what it is not - it is the absence of a compulsion or coercion to act. Defining free will by what it is, free will is the ability for up until the very moment until an action is committed, to have the ability to do otherwise.

We can consider free will to have three conditions:

- the “ability to do otherwise”

- “control over one’s choices”, and

- “responsiveness to reasons”

A decision can’t be free if it is a random choice, it must be rationally motivated (8,9).

A few other worthwhile distinctions:

- Intentions vs. urges

- Proximal vs. distal decisions

Proximal decisions are made in the moment and executed in the moment, while distal decisions are made in the moment but executed in the future. Most of the experiments neuroscientists have conducted deal with conscious states associated with simple manual actions, which corresponds to the “proximal decisions”, and was first put forward by Searle in 1983 (13).

Thalia Wheatley, Professor of Psychological and Brain Sciences at Dartmouth, defines free will as “I can choose otherwise in the moment” (14). In contrast Peter Tse, also a Professor of Psychological and Brain Sciences at Dartmouth, defines free will as “I can choose otherwise in the future” (14). Tse thinks free will is executed in deliberate decisions like “where am I going to go to college, who am I going to marry”, etc. Tse believes we can choose otherwise, not in the present, but in the future. Free will lies in planning, evaluating, and choosing future actions (14). The precise definition of free will is open to debate, and experiments typically can only probe the proximal dimensions of conscious intention.

Five Seminal Papers on the Neuroscience of Free Will

1983

Seminal Paper #1: Libet

Benjamin Libet’s work is seen as one of the most innovative and courageous attempts to rebuff the existence of free will. Libet’s claim is that brains unconsciously make decisions that people later on become aware of. In his words, “the brain ‘decides’ to initiate or at least prepares to initiate certain actions long before there is any reportable subjective awareness that such a decision has taken place” (1). Libet did believe in a constrained type of free will that Ramachandran called, “free won’t”, which is that free will does not initiate actions, but rather is the capability to prevent or “veto” certain actions. The key result in Libet’s paper was that he showed for the first time that neural preparation for action precedes the conscious feeling of being about to act. From this he concludes that brain activity therefore causes conscious intention rather than the other way around (1).

In Libet’s experiment, subjects are seated in chairs and connected to EEGs and electrical myography to measure conductivity on the scalp and to observe the muscle burst. Subjects were instructed to make a voluntary movement (to flex their wrist when they felt the urge to do so), and to report the spot on a fast clock when the subject first became aware of their intention to flex (the time of their “conscious will”). The average time of this ‘W judgement’, as Libet called it, was 206 ms before the onset of muscle activity. During the same trials, Libet also measured the readiness potential (RP), which is the preparatory brain activity preceding voluntary action. The key finding of the study was that RP onset preceded W judgement by several hundred milliseconds. This suggested that the initiation of action involves an unconscious neural process, which eventually produces the conscious experience of intention. From this, Libet concluded that conscious intentions occur as a result of brain activity, and that conscious intentions do not cause brain activity.

Criticisms of Libet

Libet’s experimental results were widely contested, with three major categories of criticism emerging.

The first major criticism was that the “readiness potential” (RP) that is generated by the SMA and measured during the experiment only provides information about the late stages of motor planning. This calls into question whether the SMA is truly the site where the decision for a movement originates, or whether other sites are involved in unconscious preparation of the decision (which had been demonstrated in studies on conscious action planning) (10,11,12).

The second major criticism was around measurement error: the time delay between the RP signal and the decision was only a few hundred milliseconds (1, 9), additionally the coarse resolution of the measurement instruments also called into question the results in some detractors eyes. Critics argued that inaccuracies in the measurement of the decision time could credibly lead to the small observed timing lead of brain activity to intention (9,10). Others argued the small lead of brain activity to intention could also have been due to how the subjects divided their attention between the clock and their subjective experience of when the intention to move emerged (11).

The third category of criticism dealt with the significance and impact of the finding (does a meaningless decision like when to flex your wrist carry weight to inform our understanding of how deliberate conscious decisions are made)? Critics argued that the temporal order of brain activity and reported subjective experience is not reliable evidence for causation.

Irrespective of the controversy, Libet’s experiment spawned an entire generation of investigators to mimic his approach. Many studies that followed sought to design a more precise version of the original Libet experiment that addressed the limitations surfaced by the critics. Follow on studies (see Soon et al. discussed later) study decision making in a game context (to demonstrate that decisions of more consequence, where motivation and stakes are involved) produce similar results. Other researchers focused on obtaining higher resolution data, by using subjects going through surgery for epilepsy to implant electrodes close to the brain to monitor activity more precisely (without the dampening of the signal produced by measurements taken on the surface of the skull) (see Fried et al. discussed later). Investigators have probed other angles, such as what happens to the signature of brain activity when we remove authorship, so that the subject has no agency for their action. Does the neural activity look the same. Does becoming aware you are in control matter? Does the neural activity look different?

Creatively, Wheatley at Dartmouth used hypnosis to take away the conscious awareness that the subject was about to move. She found that the neural activity between conscious and unconscious activity is largely overlapping. From this, she concludes conscious awareness does not play a role in simple acts like squeezing a ball, but it doesn’t mean conscious awareness doesn’t play a role in all acts (14).

1991

Seminal Paper #2: Fried

Functional organization of human supplementary motor cortex studied by electrical stimulation

Itzhak Fried was a neurosurgeon at Yale University and he studied the effect of modulating the amount (low vs high) of direct stimulation at several frontal sites in the brain, the area of most significance being the supplementary motor area (SMA), on the subjects feeling of an urge to move. The key result of the work was that low level stimulation resulted in the feeling of an urge to move a specific body part and intense stimulation resulted in an actual movement of that same body part.

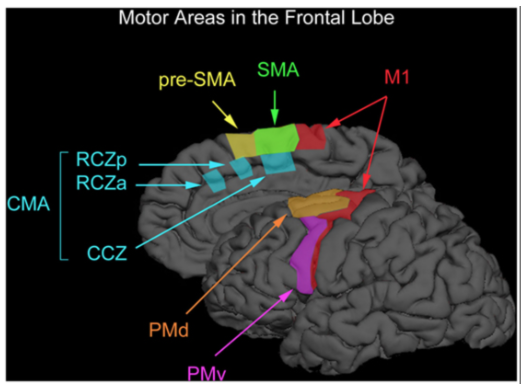

Diagram illustrating the location of the pre-SMA and SMA, image credit: Thinking, Walking, Talking: Integratory Motor and Cognitive Brain Function

Over a century prior to this study, in the 1880’s, a group of scientists (Munk, Horsley, and Schafer) had shown that stimulation of the SMA elicited movements of the head, trunk, and upper extremities in monkeys. In the 1980s, intracortical microstimulation in monkeys produced more minute, specific, orofacial, eye, and head movements (3).

While the primary motor cortex was recognized at the time to be somatotopically organized, there was debate around whether the supplementary motor cortex was also organized this way, with experimental results varying among authors and by species (3). Somatotopy refers to the correspondence of an area of the body to a specific point on the cortex, for instance fingers being controlled by a specific region of tissue. Areas that have fine control (for example fingers) have larger portions of the somatosensory cortex while areas that have coarse control (for example the trunk) have smaller portions. The seminal finding of this work was that it was the first systematic study of the human SMA using electrical stimulation mapping to demonstrate conclusively that the SMA is somatotopically organized (3).

The subjects were 13 patients being evaluated for epilepsy surgery because of persistent seizures who were implanted with a subdural electrode array over a few days. The investigators used an electrical stimulation protocol that stimulated 299 regions and obtained responses in 129 of those sites. The majority (81) responses were overt movements (subcategorized into simple, regional and complex), in the minority case, the stimulation resulted in the subjective sensory response of feeling: the urge to move, anticipating movement, a tingling sensation. The investigators were also able to stimulate vocalization as well as speech arrest. This study was the first to report that low level stimulation could produce the “urge” to perform a movement, and has obvious ramifications to the idea of free will, especially in light of Libet’s work.

Criticisms of Fried

Limitations of the work have to do with the degree of stimulus control and range. For instance, surface stimulation and current spread caused two thirds of the responses in the study to involve more than one extremity or body region. This issue of current spread makes it difficult to localize a precise movement to a site in the SMA.

2007

Seminal Paper #3: Brass

Marcel Brass is an experimental psychologist at Ghent University in Germany. Brass and his colleagues used functional magnetic resonance imaging, fMRI, to identify a candidate region in the human brain involved in the decision to “do” or “not do” an action (4). Prior to this work, the fronto-median cortex had been identified as the site for the network of intentional action (Cunnington, Ball, Lau). This network is involved in forming intentions about when and how to act, as well as generating the conscious experience of intending (Fried, Lau). However, prior to this work, few studies investigated the neural basis of the decision to act or not to act. The distinction is important, since societies require both physical action and intention to act to attribute moral and legal responsibility.

In Brass’s study, 15 participants executed six blocks with 20 trials each where they were asked to press a key on some trials, while in other trials they prepared (had the intention to perform the action) but cancelled it at the last moment. Subjects were also asked to pinpoint the time at which they first felt the intention to act, which was a mean of -141ms on action (key press) trials. The focus was to compare the trials where the subject intentionally inhibited the action to the trials where the subject intentionally executed the action. Using the participants’ estimates of when they experienced the conscious intention to make actions (that they then cancelled) along with the fMRI data, the investigators were able to localize the voluntary inhibition of voluntary action to the anterior frontomedian cortex. The data they collected suggested that the inhibition of intentional action involves a different cortical area than the intentional execution of action.

The study was the first to uncover the neural correlate to the “veto process”. Libet hypothesized that while the brain unconsciously initiated an action, the conscious mind could intervene and “veto” these unconsciously initiated action plans. The process of “last-minute” inhibition is compatible with a conscious experience of intending to act. The study suggests that some parts of the inhibition process may occur after the intention to perform an action has become conscious.

2007

Seminal Paper #4: Lau

Manipulating the experienced onset of intention after action execution.

Hakwan Lau is a behavioral neuroscientist and Professor of Psychology at UCLA. Lau’s work attempted to manipulate conscious intention. He examined the possibility that the reported onset of intentions is determined by neural activity that takes place after action execution. This non-intuitive hypothesis had not been tested before. The motivation for this study was to disprove the existence of a conscious will. We experience a strong sense of conscious control when generating spontaneous motor actions. This experience has been challenged as ‘‘illusory’’ by Daniel Wegner, a Professor of Psychology at Harvard, and others. In order to establish that the conscious will is illusory, one strategy is to show that intentions arise after actions, which would demonstrate that intentions cannot cause actions (5).

With 10 subjects, two task conditions were organized into eight 30-trial blocks for a total of 240 trials per subject. Lau used transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) over the preSMA just after action and observed a significantly advanced reported time of conscious intention. The paper suggests that the experience of conscious intention reflects a weighted combination of a number of neural signals, including preparation, execution and, perhaps, afferent feedback. The TMS condition that was induced in the experiment adds neural noise to the later components, leading to increased weighting for earlier, preparation related components in generating conscious experience.

2008

Seminal Paper #5: Soon

Unconscious determinants of free decisions in the human brain.

Soon demonstrated a truly astonishing result, that seems to definitively settle that free will does not exist. Using a novel pattern-classification algorithm on fMRI data, Soon and his team were able to predict whether subjects would push a right or left button 8 seconds before the action was made, and before the subject was consciously aware of which decision he intended to make.

Soon’s team developed a classifier (Soon uses the language ‘decoder’) that was trained to predict the outcome of the subject’s motor decision given fMRI data. The researchers used statistical techniques to analyze how much predictive information was encoded in the local patterns of fMRI signals of each brain region for the specific outcome of the motor decision (left or right button). The analysis was conducted in each region at various time points - both before and after the motor decision had reached conscious awareness. This approach surmounted frailties of previous studies in that it permitted the study of the long-term determinants of human intentions that precede the conscious intention. Prior work was only capable of examining a few hundred milliseconds before conscious action (specifically in examining the SMA). The other benefit of this approach was that it permitted the separate assessment of each brain region to determine in an unbiased and comprehensive way how much information each region contained about the outcome of a motor decision.

Overall, Soon’s team found two especially predictive brain regions that foretold whether the subject was about to choose the left or right response prior to the conscious decision. The first region (BA10) is in the frontopolar cortex, and the predictive fMRI signals from this region were present 7 seconds before the subject’s motor decision. The second region was located in the parietal cortex stretching from the precuneus to the posterior cingulate cortex. The team also attempted to predict the timing of the motor decision. Soon found that the time decision information was present in the fMRI data of the pre-SMA and SMA as early as 5 seconds before the motor decision.

Overall the key finding of Soon’s landmark work was the isolation of two specific regions in the frontal and parietal cortex of the human brain whose fMRI data predicted the outcome of a motor decision the subject had not yet consciously made. While prior studies (Libet, etc) were criticized for timing inaccuracies related to reporting the onset of awareness, the same criticism cannot be made for Soon’s study since the lead times are so much greater. Thus, Soon concludes that a network of high-level control areas can begin to shape an upcoming decision long before it enters awareness.

Remaining Challenges

The assumption behind the bulk of the empirical evidence against free will is that conscious decision takes place at an instant which can be compared with the neural activity corresponding to it (8). Yet, we still do not have a good model for how the conscious mental processes are related to the neural processes (9, 11).

- If the brain activity causes the conscious awareness of an intention, what causes the “original” brain activity (that spurred the consciousness)?

- Can the precursor brain activity that has been observed experimentally be compared to the computational construct of speculative execution (we operate on auto-pilot until we notice something is errant)?

- How does the brain enable conscious causal control of our actions and decisions?

- How do our conscious intentions lead to actions? Can the results of the Libet-type experiments (that involve inconsequential motor movements) generalize to more deliberate decisions?

- Can we develop experimental models to understand the role of conscious intention in longer ranger decision making (such as choosing a career or spouse)?

- The stochastic models and the models of evidence accumulation consider decision as the crossing of a threshold of activity in specific brain regions: is there a way to experimentally validate this theory?

Impact

Social psychologists have studied how people respond to being told free will does not exist. Overall, people tend to behave worse when they subscribe to deterministic beliefs. Kathleen Vohs and Jonathan Schooler, a psychologist and Professor of Brain Sciences at the University of California, Santa Barbara conducted a study and found that subjects who read a scientific article saying free will did not exist cheated more than controls or people who were told free will did exist (15). Another study at Florida State lead by Roy Baumeister, found that participants who read statements indicating free will did not exist (this time not from scientists), as opposed to controls who did not read anti-free will statements, behaved less compassionately in a following task. The next task was to distribute snacks, and subjects were told people in this group were very sensitive to spicy food, but had to consume everything served to them. The study found that subjects who were told free will did not exist would serve out significantly more spicy salsa to people compared to controls. Baumeister theorizes that our moral responsibility for our actions decreases with the belief that free will is an illusion. If we think we are not blameworthy for your actions, why not go for the more aggressive action? Why restrain ourselves if free will truly is an illusion?

Credits

Credit for the good stuff goes to Surya Ganguli and Dan Yamins. Mistakes are mine.

Citations

-

Passingham, R. E. Two cortical systems for directing movement. Ciba Found. Symp. 132, 151–164 (1987).

-

Haggard, Patrick. “Human volition: towards a neuroscience of will.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 9.12 (2008): 934.

-

Walter, H. (2001). Neurophilosophy of Free Will: From Libertarian Illusion to a Concept of Natural Autonomy. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

-

Wegner, D.M. The mind’s best trick: how we experience conscious will. Trends Cogn. Sci. 7, 65–69 (2003).

-

Haggard, P. Conscious intention and motor cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9, 290–295 (2005).

-

Searle, J.R. (1983) Intentionality, CUP

-

https://pbs.dartmouth.edu/do-we-have-free-will